Imam Abu Hanifa Nuʿman bin Thabit (699–767 CE) is one of the most influential figures in Islamic history, renowned as the founder of the Hanafi madhab (school of law) – the oldest and most widely followed of the four Sunni schools of jurisprudence.

Often honored with titles like Al-Imam al-Aʿzam (“The Greatest Imam”), Abu Hanifa’s contributions laid the foundation for a rich tradition of Islamic scholarship. His school’s emphasis on reasoned analysis alongside scriptural sources has made it the largest legal school, with adherents comprising roughly one-third of the world’s Muslims!

In this article, we will explore Imam Abu Hanifa’s early life in Kufa, highlight inspiring stories from his life (including his principled refusal of high office and its consequences), explain the Hanafi methodology of jurisprudence – especially the use of qiyās (analogical reasoning) and istiḥsān (juristic preference) – and outline key legal principles of the Hanafi school. We will also compare the Hanafi madhab with the other three Sunni madhhabs (Maliki, Shafiʿi, and Hanbali) in terms of methodology and global distribution.

Early Life in Kufa: From Merchant to Scholar

Abu Hanifa was born in the year 80 AH (699 CE) in Kufa, a garrison city in present-day Iraq. Kufa at that time was a vibrant center of Islamic learning, home to many Companions of the Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him) and their students.

Imam Abu Hanifa’s family were of Persian origin – his father Thabit bin Zuta hailed from the region of Kabul (in today’s Afghanistan) – and were successful cloth merchants by trade. Growing up in a prosperous and religious household, the young Nuʿman (Abu Hanifa’s given name) memorized the Quran and helped in the family business. His nickname “Abu Hanifa” (“father of Hanifa”) is said to derive from the word ḥanīf (upright or true believer), reflecting his devotion and sincerity in faith.

As a youth, Abu Hanifa was known for his sharp intellect and honesty. An oft-cited anecdote describes how a local scholar, ash-Shaʿbi, noticed him and encouraged him to pursue formal Islamic studies. Taking this advice to heart, Abu Hanifa shifted from full-time trade to seeking knowledge. He began attending the study circle of the famed scholar Hammad ibn Abi Sulayman in Kufa. Abu Hanifa would remain Hammad’s devoted student for about 18 years, mastering the fiqh (jurisprudence) of the Iraqi scholars. Upon Hammad’s death, Abu Hanifa, at around 40 years old, was recognized for his learning and assumed leadership of the study circle, teaching and issuing legal judgments.

Notably, Abu Hanifa lived within the generation after the Prophet’s Companions, and some reports suggest he met and learned from at least a few Companions, which would make him among the Tābiʿūn (Successors). In fact, one traditional source lists sixteen Companions from whom Abu Hanifa transmitted hadith, including Anas ibn Malik, Jabir ibn Abdullah, and Abdullah ibn Masʿud’s son (Abdullah ibn Abi Awfa), among others. While these reports are debated, they underscore the connection of Abu Hanifa’s knowledge to the early generations of Islam.

Abu Hanifa’s pursuit of knowledge was not confined to Kufa. He traveled to the Hijaz (Mecca and Medina) for Hajj and took the opportunity to study with renowned scholars there. It is said he learned from ʿAta ibn Abi Rabah in Mecca and the great Imam Jaʿfar al-Sadiq in Medina, among others. This broad exposure enriched his scholarship, blending the Kufan emphasis on reason with the Hijazi emphasis on hadith.

Despite his growing scholarly stature, Imam Abu Hanifa maintained his business as a silk merchant for many years, ensuring an independent income. His honesty in trade was legendary – numerous stories tell of his scrupulous fairness with customers and his insistence on transparency in business dealings. This ethical grounding in day-to-day life complemented his scholarly endeavors, producing a faqīh (jurist) who deeply understood people’s practical needs.

By his middle age, Abu Hanifa was widely recognized as one of Kufa’s foremost scholars. Students gathered from far and wide to learn from him. Among his most famous pupils were Abu Yusuf (who would become the chief judge of the Abbasid Empire), Muhammad al-Shaybani, and Zufar ibn Hudhayl. These students would later compile and spread Abu Hanifa’s views, transforming his teachings into the first codified school of Islamic law in Sunni Islam.

Despite his scholarly eminence, Abu Hanifa remained humble and God-fearing. He was known for spending long hours in worship and for his generous support of students and the poor.

Integrity and Principle: Refusal of High Office and Imprisonment

One of the most compelling stories from Imam Abu Hanifa’s life is his refusal to serve as a government judge, a decision that illustrates his principled character and commitment to justice. During his lifetime, the Muslim world saw the transition from the Umayyad Caliphate to the Abbasid Caliphate. Abu Hanifa, as a prominent scholar, was offered high judicial positions by the rulers of both dynasties – offers he flatly declined on grounds of conscience.

Under the Umayyads, the governor of Iraq, Yazid ibn Hubayra, pressed Abu Hanifa to accept the post of qāḍī (judge) of Kufa. Imam Abu Hanifa refused, knowing that such a position might require compromising his independent judgment to please the authorities. Ibn Hubayra reacted by having the Imam flogged: Abu Hanifa was whipped 110 lashes (10 per day for eleven days) as punishment for his refusal. Even under this duress, the Imam did not relent, and eventually the governor let him go, unable to sway his resolve.

A few years later, in 763 CE (146 AH), the new Abbasid Caliph Abu Jaʿfar al-Mansur sought to co-opt Imam Abu Hanifa’s influence by offering him the post of Qāḍī al-Qudhāt – Chief Judge of the entire caliphate. Again, Abu Hanifa declined. He is reported to have told the caliph that he did not consider himself fit for the position, to which al-Mansur angrily accused him of lying. The Imam’s quick retort has become famous: “If I am lying, then my statement is doubly correct – for a liar cannot be fit to be a judge!”. This incisive reply only infuriated al-Mansur further. Determined to make an example, the caliph imprisoned Abu Hanifa for his refusal.

In prison, Imam Abu Hanifa was again subjected to flogging. Some reports say he was brought out in public and whipped ten lashes each day. Despite the hardship, he remained steadfast in his decision not to serve unjust power. After some time – perhaps due to harsh conditions or even poisoning at the caliph’s order – Imam Abu Hanifa grew weak.

In 767 CE (150 AH), at around 70 years of age, Imam Abu Hanifa died in captivity, reportedly while in a state of prostration in prayer . Many Muslims consider him a martyr (shahīd) for dying under wrongful imprisonment.

The news of his death caused an outpouring of grief in Baghdad. It is said that tens of thousands of people attended his funeral, so much so that the Janazah (funeral prayer) had to be repeated multiple times to accommodate all the mourners.

He was buried in the al-Khayzuran Cemetery in Baghdad’s Adhamiyah district, and a mosque was later built at the site of his tomb (today known as Abu Hanifa Mosque).

The Abbasid ruler, al-Mansur – perhaps feeling remorse – reportedly prayed for Abu Hanifa when he heard of the Imam’s final request not to be buried on any land usurped by the caliph.

Through this courageous stance, Imam Abu Hanifa left a lasting lesson in upholding truth and integrity. He demonstrated that Islamic scholars must be guided by principle and must check injustice, even at great personal cost.

The Hanafi School of Jurisprudence: Methodology and Key Principles

Imam Abu Hanifa’s true legacy lies in the school of Islamic jurisprudence that grew from his teachings. The Hanafi madhhab is characterized by a balance between reverence for the divine texts and the use of human reason to apply those texts to new situations.

Abu Hanifa and his students were pioneers in developing Uṣūl al-Fiqh (principles of jurisprudence) – systematically defining how legal rulings should be derived from the Quran and Sunnah. This methodology allowed for both consistency and flexibility in legal reasoning, which was essential as Islam spread to diverse lands and cultures.

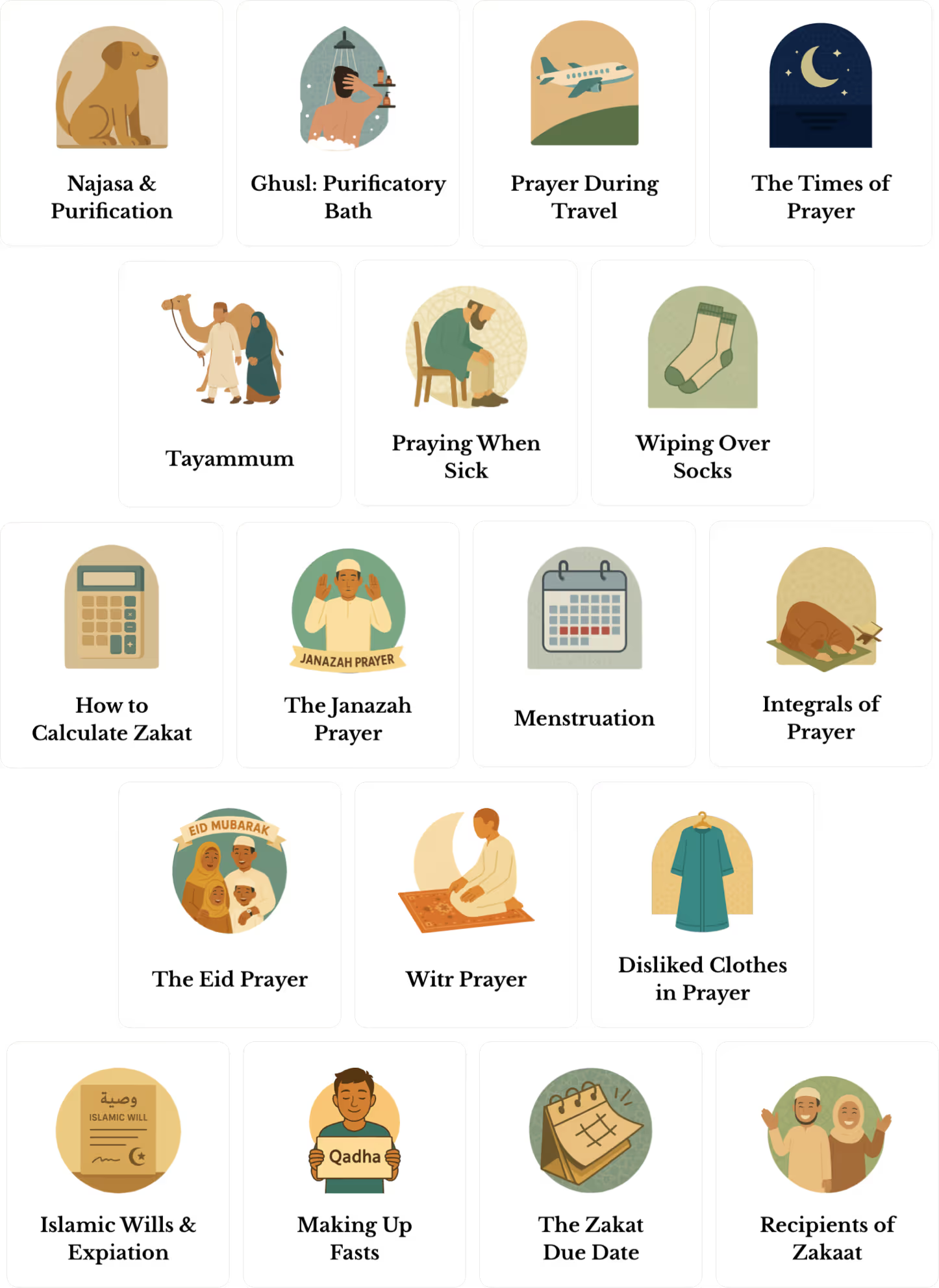

Below are some of the key principles from Hanafi fiqh (school of thought):

Primary Sources (Qur’an and Sunnah)

Like all Sunni schools, the Hanafis give primacy to the Qur’an and the authentic Sunnah (teachings and practices of Prophet Muhammad). These are the first and foremost references for any legal issue. Imam Abu Hanifa was well-versed in hadith, but he applied a critical lens to solitary narrations (khabar al-aḥād). He held that if a hadith’s content appeared to conflict with the Quran or widely established principles, or if the narrator’s own actions contradicted the report, then one should be cautious in directly applying it. This cautious approach ensured that the spirit of the law was not lost in literal application. When clear texts from the Qur’an or consensus Sunnah were available, Hanafis adhered to them strictly; it was in the absence of explicit textual guidance that the school’s distinguishing methods came into play.

Consensus (Ijmaʿ) and Precedent

The Hanafi school strongly values ijmāʿ, the consensus of the Companions and early generations. Abu Hanifa deferred to the collective agreement of the Sahabah (Companions) on any matter; he famously said that if something was the opinion of a Companion, he would not choose an opinion outside of that. However, on issues where the Companions differed or there was no clear consensus, Abu Hanifa considered himself and other qualified scholars entitled to exercise independent reasoning (ijtihād). He did not consider the opinions of later Tabiʿīn (Successors) after the Companions as binding, asserting that beyond the generation of the Sahabah, “the opinion of any person is as good as any other”. In practice, this meant the Hanafis often examined the juristic opinions transmitted from leading jurists of Kufa – like Ibrahim al-Nakhaʿi and others – and built upon that precedent, unless they found stronger evidence to the contrary.

Qiyas: Thinking by Analogy

Perhaps the hallmark of Hanafi fiqh is its extensive use of qiyās, or analogical reasoning. Qiyās entails extending the ruling of an established case to a new case because they share an underlying effective cause (ʿilla). Imam Abu Hanifa systematized the use of analogy so that Islamic law could provide answers even for unprecedented scenarios.

- For example, the Qur’an explicitly forbids wine due to its intoxicating effect; by qiyās the same prohibition is extended to all intoxicants, even those (like distilled liquor or narcotics) not explicitly mentioned in scripture, because the reason – intoxication – is the same.

The Hanafis’ greater usage of qiyās than other schools is a distinctive feature noted by scholars. This rational method allowed the Hanafi school to address new social issues in a logical, principle-based manner.

It’s important to note that qiyās is employed only when no clear text or consensus is available on an issue – it is a tool to ensure the law can evolve faithfully in new contexts, guided by the intent of the Shariah.

Istihsan: Prioritizing Equity

Another key feature of Hanafi methodology is istiḥsān, often translated as “juristic preference” or “equity.” This is a technique whereby a jurist may depart from a strict analogical result to adopt a ruling that better serves justice or public interest, based on stronger secondary evidence or considerations. Far from an arbitrary whim, istihsan is described by the Hanafis as “leaving one opinion for a stronger one.” In practice, it means that if applying qiyās in a given case would lead to an overly harsh or unfair outcome, the jurist can seek an alternative ruling grounded in the objectives of Shariah.

- For instance, by pure analogy one might argue that contaminated well water cannot be used for ablution; however, Hanafis invoke istihsan to permit its use after reasonable purification steps, recognizing the necessity for people who have no other water source.

- Another classical example: analogy might forbid certain forward sales (since one is selling something not yet in one’s possession), but considering public welfare, Hanafis and others allowed salam (advance payment contracts) by way of exception, as it facilitated agriculture and trade

Istihsan, thus, serves as a safety valve in the legal system – ensuring that rigidity does not override maṣlaḥa (public interest) and that the law remains compassionate and practical.

It was on this principle that Imam Abu Hanifa’s school was sometimes criticized by others (Imam al-Shafiʿi once questioned it as “moving away from evidence to personal preference”), but the Hanafis defended it as choosing the better among evidence-based solutions. In fact, other schools have similar concepts under different names (like istislāḥ in the Maliki school); all aimed at preserving higher objectives of the law.

Local Custom (ʿUrf)

The Hanafis also give consideration to prevailing custom (ʿurf or ʿādah) as a secondary source, so long as the custom does not contravene Islamic principles. This means that cultural practices and norms can influence legal judgments in the Hanafi school in cases where the scripture is silent. Recognizing custom lends the Hanafi madhhab a degree of cultural adaptability.

Scholars note that Hanafis’ emphasis on acknowledging local customs may partly explain why the school spread early on among diverse non-Arab societies – it could accommodate their customary practices within the framework of Shariah.

- An example might be recognizing regional business practices or forms of contracts as valid so long as they don’t conflict with Islamic conditions for contracts.

Key Principles of Hanafi Fiqh:

In summary, the methodology of the Hanafi school can be outlined by the following hierarchy of principles:

- Qur’an – the revealed word of God, primary and infallible source of law.

- Sunnah – the teachings and practices of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), as recorded in hadith. Authentic prophetic guidance is second only to the Qur’an.

- Ijma (Consensus) – especially the consensus of the Prophet’s Companions. A ruling agreed upon by the early scholarly community is given great weight.

- Qiyas (Analogical Reasoning) – extending rulings to new cases by identifying common causes, used when direct texts are lacking. Hanafis applied qiyas extensively to deduce law for new situations.

- Istihsan (Juristic Preference) – departing from strict analogy to a stronger, more equitable ruling in special cases, to serve the higher objectives of justice and public welfare. Sometimes termed “equity in Islamic law,” istihsan prevents unreasonable or harmful outcomes by allowing exceptions based on sound juristic evidence.

- Urf (Custom) – acknowledged local customs and usage can be incorporated into legal reasoning if they do not violate Islamic tenets. This principle helps make the law contextually relevant and eases implementation across cultures.

- Sayings of Sahaba – (related to ijma) the individual opinions of the Prophet’s Companions are respected; if a clear solution was provided by a Companion, the Hanafis would often adopt it in absence of other evidence. However, no later person’s opinion is binding, preserving the Imam’s freedom of ijtihad beyond that.

By prioritizing these principles in order, the Hanafi madhhab managed to achieve a remarkable balance: it remained firmly rooted in scripture and early Islamic tradition, yet it was flexible enough to address complex new issues through reasoned analogy and considerate exceptions. This approach led the Hanafi school to be seen as one of moderation and adaptability, offering ease and practicality while upholding the core of the Shariah. Historically, this made the Hanafi school particularly suited to cosmopolitan and diverse societies – from the courts of the Abbasid and Ottoman empires to the marketplaces of Central and South Asia.

Imam Abu Hanifa's Legal Principles in Modern Context

How key Hanafi principles apply to contemporary issues faced by Muslims today:

This table highlights how Imam Abu Hanifa's principles, though rooted in the past, continue to offer practical solutions for contemporary challenges. His emphasis on public welfare, custom, and reasoned analysis empowers Muslims to engage with the modern world while adhering to their faith.

His teachings provide a practical path for Muslims to live their faith in a complex world. This isn't just a historical footnote; it's a living tradition that offers guidance and comfort to millions navigating the complexities of modern life. It's a testament to his foresight that his principles remain as valuable today as they were centuries ago.

Comparison with Other Sunni Madhabs: Methodology and Global Spread

While all four major Sunni madhabs share the same fundamental belief system and sources, they developed distinct methodologies (uṣūl) in jurisprudence. These methodological nuances led to differences in certain legal rulings and practices, although the vast majority of core rulings remain common among them.

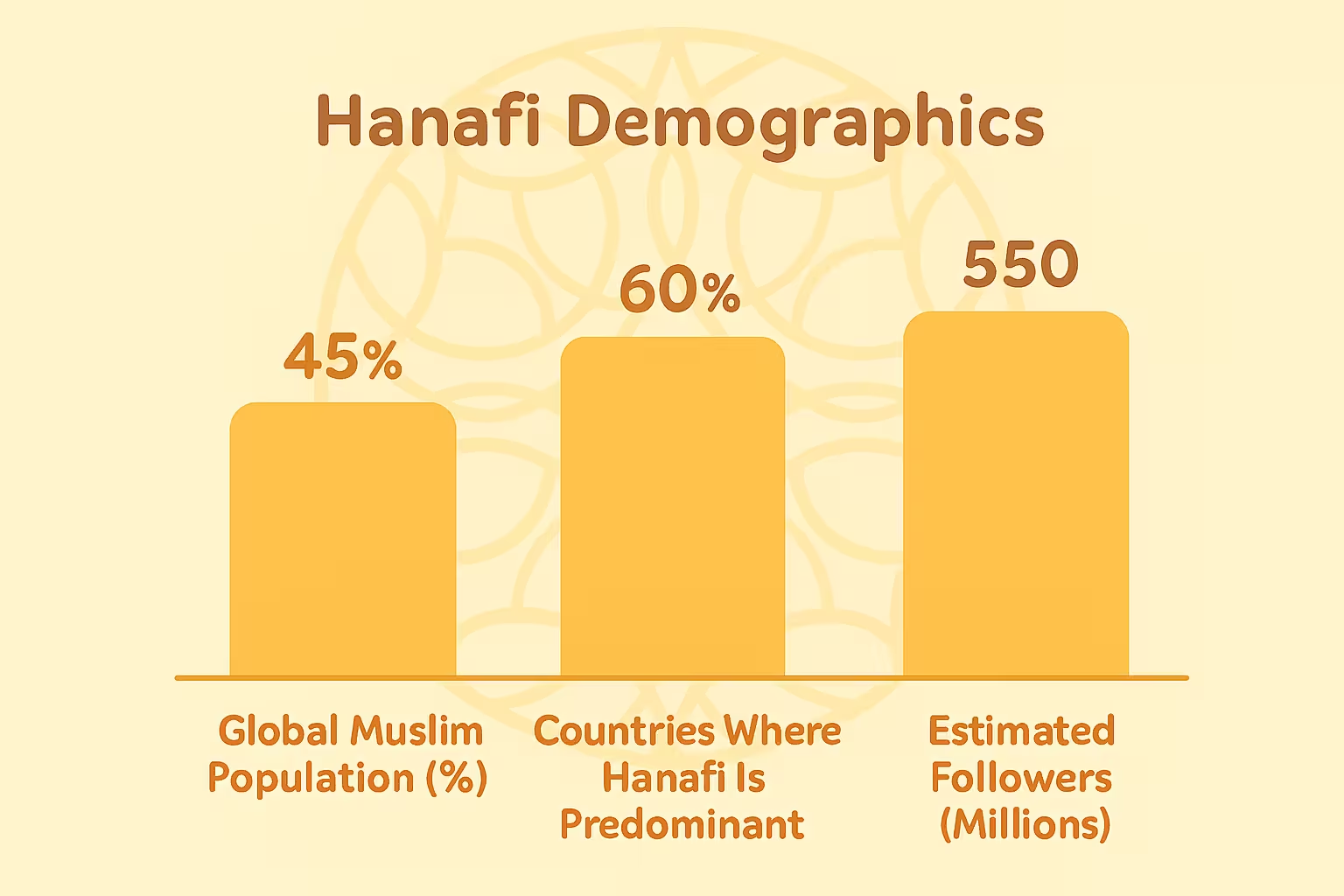

The infographic above illustrates the global impact of the Hanafi school. It highlights the estimated number of followers, the percentage of the global Muslim population they represent, and the school's prevalence across various countries. The Hanafi school's influence is clear, with approximately 550 million followers, representing around 45% of the global Muslim population. It holds a prominent position in roughly 60% of Muslim-majority countries.

To better understand the distribution of Islamic legal schools, let's take a look at the following table:

Here we compare the Hanafi school with the Maliki, Shafiʿi, and Hanbali schools in terms of their approaches to deriving law, as well as where these schools historically flourished around the world.

Methodological Differences in Brief

- Hanafi vs. Maliki: The Maliki school, founded by Imam Malik in Madinah, likewise bases rulings on the Qur’an, Sunnah, and consensus, but it has a distinctive reliance on the practice of the people of Madinah (ʿamal ahl al-Madinah) as an authoritative guide. Malik considered the lived practice of the early Madinan community – which included many Companions – as a powerful indicator of Sunnah. Thus, if an authentic hadith seemed at odds with the established practice passed down in Madinah, Malikis might favor the Madinan practice as representative of the Prophet’s true teaching.

- Malikis also employ istiṣlāḥ (maslahah), reasoning based on public interest, in cases where neither scripture nor consensus directly apply – similar to Hanafi istihsan, but more formally emphasizing general welfare.

- Both Hanafis and Malikis allow a form of “legal flexibility” – Hanafis via istihsan, and Malikis via maṣlaḥah mursalah (unrestricted public interest) – to ensure the law serves its purpose. However, Malikis are generally less inclined toward abstract analogical reasoning than Hanafis; they ground rulings in precedent and the common good, and they are known for the principle of sadd al-dharā’iʿ (“blocking the means” to wrongdoing).

- For example, Maliki jurists often forbid transactions or actions that are technically permissible but could lead to haram outcomes as a precaution. Hanafis, by contrast, were somewhat more open to ḥiyal (legal stratagems or “work-arounds”) in transactions, provided no clear law was broken. This reflects a subtle difference: Maliki law’s protective stance versus Hanafi law’s accommodative flexibility.

- Hanafi vs. Shafiʿi: The Shafiʿi school, founded by Imam al-Shafiʿi, came slightly later and was in part a response to what Imam Shafiʿi saw as overreliance on local practice or speculative reasoning. Shafiʿi’s approach placed a strong emphasis on textual evidence. He famously systematized uṣūl al-fiqh in his book Al-Risāla. The Shafiʿi school gives primacy to Qur’an and authentic Sunnah, then consensus, and then qiyās – and tends to be skeptical of concepts like istihsan or excessive use of custom in deriving law.

- Shafiʿis argue that if a ruling is supported by a clear sahih hadith, it should be followed even if it contrasts with local custom or personal rational preference. In fact, Imam Shafiʿi is known for the quote: “If a hadith is authentic, then that is my madhhab.” Thus, Shafiʿi methodology is sometimes seen as more text-centric in contrast to Hanafi rationalism.

- That said, Shafiʿis do use analogy similarly to Hanafis, but within a tighter framework that Shafiʿi defined, and they did not formalize “juristic preference” as a separate principle (preferring to subsume equitable considerations under qiyās or general principles of necessity). In practice, this means Shafiʿi jurists might arrive at different conclusions on certain issues – for example, in ritual prayer or commerce – based on a stringent reading of hadith where Hanafis might invoke analogy or permissive principles for ease. Nonetheless, the outcomes between Hanafi and Shafiʿi fiqh are often very close; both are robust traditions that have cross-pollinated over time. Imam Shafiʿi, who studied under Imam Malik and also met students of Abu Hanifa, had immense respect for Abu Hanifa’s intellect, even as he critiqued some methods.

- Hanafi vs. Hanbali: The Hanbali school, founded by Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, is generally seen as the most textualist and traditionist of the four. Imam Ahmad, a master of hadith, placed overwhelming emphasis on the Qur’an, Sunnah, and the athar (reports) of the Salaf (early generations). The Hanbali approach will use Qur’an and hadith evidence to the furthest extent possible, even taking weaker hadith in absence of stronger ones, rather than resort to personal reasoning. Only when absolutely necessary will Hanbali jurists resort to qiyās – and they do not utilize istihsan or give independent weight to custom in the way Hanafis do.

- Hanbalis also strongly uphold sadd al-dharā’iʿ (blocking means to sin) similar to Malikis. For example, where a Hanafi might allow a technically lawful tactic to avoid a difficult rule (so long as it’s not explicit cheating), a Hanbali might disallow it fearing it undermines the spirit of the law. The result is that Hanbali rulings can appear stricter or more literal.

- A classic comparison: In matters of worship or food, Hanbalis often err on the side of precaution (e.g., considering something impermissible unless clearly proven permissible by text), whereas Hanafis have a principle “al-aṣl fī’l-ashyāʾ al-ibāha” (the default in worldly matters is permissibility) unless proven otherwise.

- It’s worth noting the scope of hadith acceptance: Ahmad ibn Hanbal’s school would accept a Companion’s fatwa or a very weak hadith before accepting pure opinion. Hanafis, in contrast, were willing to use calibrated reasoning if the textual proofs were not decisive. Despite these differences, the Hanbali school and Hanafi school share many rulings, and later Hanbali scholars like Ibn Taymiyyah also employed reasoning that sometimes aligns with Hanafi-like interpretations (for instance, choosing an outcome due to istiḥsān-like considerations, even if they didn’t call it that). All four schools ultimately aim to uphold the Shariah; they mainly diverge in method, not goals.

In summary, the Hanafi madhhab is characterized by its extensive use of analogy and reason, coupled with a willingness to make exceptions for equity. The Maliki madhhab emphasizes community practice and welfare, the Shafiʿi madhhab emphasizes strict adherence to textual proofs, and the Hanbali madhhab emphasizes literal implementation of texts and vigilant avoidance of doubtful matters.

Importantly, all four schools are considered valid and orthodox in Sunni Islam – they only provide different roads to the same destination of understanding God’s law. Classical scholars often studied and respected multiple madhhabs; for example, it was not unusual for a jurist to be versed in both Hanafi and Shafiʿi fiqh debates.

The diversity in methodology has been a mercy, accommodating the Ummah’s diversity and allowing flexibility in legal opinions under different circumstances. As Imam Malik reputedly said, “The disagreement of the scholars is a source of mercy.”

Global Distribution of the Madhabs (Schools of Thought)

Over the centuries, each madhab became associated with certain regions, often due to historical caliphates and missionary scholars adopting that school. Hanafi fiqh, being the earliest codified school, spread far and wide especially under the Abbasid and Ottoman empires.

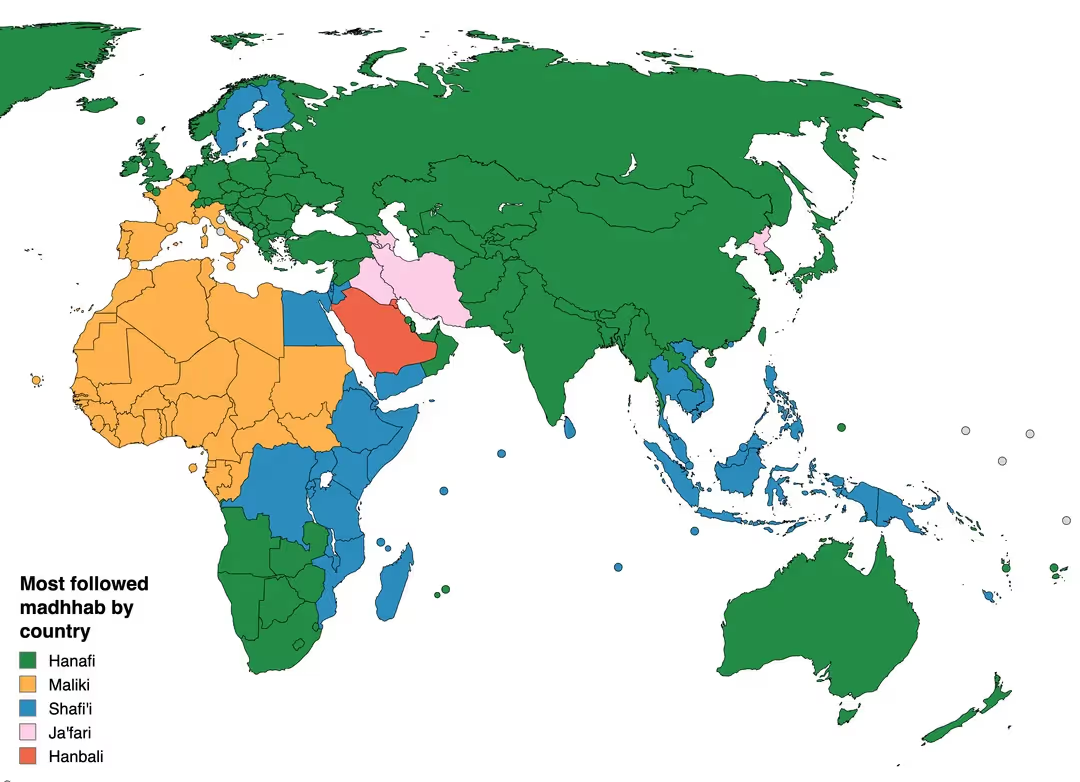

The map below illustrates the dominant madhabs in various Muslim-majority regions:

- Historically, the Hanafi school gained prominence in Iraq, Persia, Transoxiana (Central Asia), and later became the official school of the Ottoman Empire (covering Turkey, the Balkans, and Levant). It also took root in the Indian subcontinent, especially under the Mughal Empire which patronized Hanafi jurists. As a result, today Hanafi is the predominant madhhab in South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan), Central Asia, Turkey, the Balkans, and has a significant presence in parts of the Middle East (e.g., Iraq, Syria). Many Muslim communities in China also historically followed the Hanafi school via Central Asian influence. Overall, Hanafi jurisprudence is the most widely practiced, known for its flexibility which suited the diverse populations of these regions.

- The Maliki school is strongest in North and West Africa. It was the main school of Islamic Spain (Andalus) and spread across the Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya) and down into West Africa (Mauritania, Mali, Senegal, Nigeria, etc.) via scholars and trade routes. Maliki fiqh is also followed in parts of the Arabian Gulf; for example, Kuwait and Bahrain historically had influential Maliki scholars, and even in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province there were Maliki influences before. Sudan and parts of East Africa (like some communities in Chad and Eritrea) also have Maliki adherence. Wherever the legacy of early Madinan scholarship went – often carried by Maliki jurists – that became Maliki territory. Today, roughly all of North/West Africa remains predominantly Maliki.

- The Shafiʿi school became prevalent in Egypt (after Salahuddin Ayyubi’s time, Cairo became a hub of Shafiʿi learning) and spread to East Africa and Southeast Asia. Yemen, for instance, has a long Shafiʿi tradition in its southern coastal areas (while the north is Zaidi Shi’a). The Swahili coast of Africa (Kenya, Tanzania) and Horn of Africa (Somalia, Djibouti) are largely Shafiʿi due to Yemeni influence. Perhaps most significantly, Shafiʿi scholars from the Middle East reached Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines starting around the 12th century, making Shafiʿi fiqh dominant in Southeast Asia. Southern parts of India (Kerala and the Malabar coast) also had early Shafiʿi influence through Arab traders. Thus, the Shafiʿi madhhab today is prevalent in a vast arc from East Africa through Southern Arabia to South East Asia.

- The Hanbali school historically had fewer followers, but it saw a revival in the Arabian Peninsula. Hanbali fiqh was kept alive in pockets, such as by certain scholars in Syria and Iraq, but it became politically significant when the reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab in the 18th century adopted Hanbali jurisprudence and partnered with the Saudi rulers. As a result, Saudi Arabia (and to a degree its neighbors in the Gulf) became strongholds of the Hanbali school. Today, Hanbali is the officially endorsed madhhab in Saudi Arabia (though the state now mixes rulings from various schools in its codified laws). Qatar also has Hanbali influence. Elsewhere, Hanbalis remain a minority; small communities in Palestine, Syria, and Iraq adhere to it, but it’s the least geographically widespread. In percentage terms, Hanbalis comprise a relatively small portion of Sunnis, whereas Hanafis, Shafiʿis, and Malikis cover the vast majority.

It’s important to remember that these distributions aren’t exclusive or rigid. Major urban centers historically had scholars of all madhhabs. For instance, Cairo had separate courts or sections for the four schools under Mamluk rule. The Levant (Sham) region had significant Hanafi and Shafiʿi populations (the Ottomans imposed Hanafi as official, but people maintained their own practices too). Iraq and Iran before turning majority Shia had a mix of Hanafi and Shafiʿi. In South Asia, while Hanafi is dominant among Sunnis, there have always been pockets of Shafiʿis (especially on coasts) and others.

Today, global mobility means you can find all four madhhabs practiced in most large Muslim communities worldwide. Crucially, Sunnis regard all four madhabs as valid paths – a Maliki and a Hanafi praying side by side may have slight differences in how they hold their hands or how they phrase the intention of prayer, but they fully recognize each other’s prayer as legitimate. This mutual respect was emphasized by classical scholars and remains a unifying aspect of Sunni Islam.

FAQs About Imam Abu Hanifa

When was Abu Hanifah born?

Imam Abu Hanifa was born in the Hijri year 80 AH or 699 CE.

What was Abu Hanifa famous for?

Imam Abu Hanifa is famous for being the founder of the Hanafi fiqh school of thought, the largest of the four madhabs in Sunni Islam followed by over 550 million Muslims across the world.

What was the Madhab of Imam Abu Hanifa?

The Hanafi madhab (school of thought), named after him.

Was Abu Hanifa a salafi?

Salafi refers to those who follow the way of the "Salaf". Imam Abu Hanifa was one of the Tabi'un which means whislt he was not from the Sahaba who met the companions. All four imans of the great sunni madhabs are all followers of the Prophet PBUH.

Was Imam Abu Hanifa Persian?

Yes. Imam Abu Hanifah was born in Kufa (modern-day Iraq) but his family had Persian origins.

Why was Abu Hanifa jailed?

Imam Abu Hanifah was jailed in two separate scenarios, the second leading to his death in prison, for refusing high judicial positions offered to him under the Umayyad and Abbasid rulers.

Who are the 4 imams of Islam?

There are 4 great fiqh scholars in Islam. These include Imam Abu Hanifa, Imam al-Shafi'i, Imam Malik and Imam Abu Hanbal.

What is the difference between Shafi and Hanafi?

These are two of the great madhabs (school of thought). One was founded by Imam al Shaf'i and the other by Imam Abu Hanifah. They are both respected and valid madhabs to follow. They differ in the methodology they use to come to specific rulings (e.g. how to pray).

Did Imam Abu Hanifa meet any of the sahaba?

Yes, Imam Abu Hanifa is tabi'i which is the title given to those who were not from the sahaba but met one of the sahaba (a sahabi is someone who met the Prophet PBUH).

Legacy and Conclusion

Imam Abu Hanifa’s legacy is monumental. Through his intellectual rigor and commitment to principle, he paved the way for a school of law that has served the Muslim ummah for over a millennium. Often, later scholars would affectionately say that all jurists are somehow the students of Abu Hanifa, due to his early role in formulating systematic Islamic law.

Imam Abu Hanifa's two brilliant students, Abu Yusuf and Muhammad al-Shaybani, ensured that the Imam’s teachings were preserved in writing – compiling his legal opinions and the reasoning behind them. These works became reference points for judges and muftis in courts from Baghdad to Delhi. By the Ottoman era, Hanafi fiqh was refined into comprehensive law codes (like the Ottoman Mecelle) that could govern complex societies.

Yet beyond jurisprudence, Imam Abu Hanifa is remembered for his piety, generosity, and unwavering ethics. Stories of him spending entire nights in worship, or forgiving the debts of poor customers, or supporting the family of the Prophet (PBUH) during uprisings, all paint the picture of a scholar who lived by his principles. His life teaches us that knowledge and action must go hand in hand. Despite facing persecution, he never compromised on integrity – a powerful reminder for scholars and students today.

The Hanafi madhab that he founded continues to thrive, not as a stagnant set of old rulings, but as a living tradition. Contemporary Hanafi scholars build on the framework of Abu Hanifa to address modern issues – from finance to biomedical ethics – showing the enduring adaptability of his methodology. The Hanafi emphasis on reason, ease, and public interest (within the bounds of the Quran and Sunnah) makes it particularly suited for minority communities and diverse contexts, which is why it’s been so influential in places like Europe, North America, and beyond through modern fatawa.

In conclusion, Imam Abu Hanifa’s impact on Islamic scholarship is immeasurable. Understanding his life and the principles of the Hanafi school offers a window into how Islamic law balances divine guidance with human circumstances. It deepens our appreciation for the rich scholarly heritage of Islam.

All four Sunni madhhabs, including the Hanafi, collectively ensure that Muslims can live their faith in various contexts while staying true to core principles. As general Muslim readers, learning about these madhhabs and their founders like Abu Hanifa can inspire us to be more tolerant of jurisprudential differences and more appreciative of the scholars’ dedication that has preserved our religious practice.

Further Resources for In-Depth Study

For those interested in learning more about Imam Abu Hanifa and the Hanafi madhhab, here are a few avenues to explore:

- Detailed Biographies: Consider reading a detailed biography such as “Sirat Nu‘man” (Life of Nu‘man, i.e., Abu Hanifa) by Allama Shibli Nomani, which has been translated into English. This work provides rich historical context and stories from the Imam’s life. Another respected biography is Imam Muhammad Abu Zahra’s section on Abu Hanifa in his book “The Four Imams.” These works offer deeper insight into the Imam’s character, teachers, and contributions.

- Classical Texts of the Hanafi School: To dive into Hanafi jurisprudence itself, one might look at the compilations by Abu Hanifa’s students. “Al-Fiqh al-Akbar,” a short treatise on Islamic creed attributed to Abu Hanifa, is a starting point (showing his theological side). In fiqh, texts like “Kitab al-Athar” (by Imam Muhammad al-Shaybani) and “Al-Muwatta” in the narration of Imam Muhammad (a Hanafi recension of Malik’s book) contain many rulings from the early Hanafi perspective. For a more beginner-friendly overview, contemporary primers on Hanafi fiqh (covering worship, ethics, etc.) by modern scholars are widely available.

- Courses and Lectures: Many organizations offer courses on Hanafi fiqh and on the lives of the great Imams. For example, online platforms like SeekersGuidance, SunniPath, or AlMaghrib have had series on the fundamentals of Hanafi law or the biography of Imam Abu Hanifa. Tuning into such lectures can provide a guided study experience. Mosques and Islamic centers in Hanafi-oriented communities (such as those of South Asian background) often hold classes on Hanafi jurisprudence as well.

- Academic Works: If you are academically inclined, books like “The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence” by Joseph Schacht (though dated and controversial in parts) or “The Formation of the Sunni Schools of Law” by Wael Hallaq discuss how early Islamic law developed, including Abu Hanifa’s role. Brannon Wheeler’s “Applying the Canon in Islam: The Authorization and Maintenance of Interpretive Reasoning in Hanafi Scholarship”en.wikipedia.org and Nurit Tsafrir’s “History of an Islamic School of Law: The Early Spread of Hanafism”en.wikipedia.org are more focused studies on Hanafi usul and history. These can be found in university libraries for those who want a scholarly deep dive.

- Visiting Heritage Sites: If you ever travel to Baghdad, a visit to Imam Abu Hanifa’s mosque and tomb in the Adhamiyah district can be a spiritually enriching experience. The area, named after him (Al-Aʿzamiyah – “of the Great Imam”), has been a center of learning for centuries. Standing at his resting place offers a tangible connection to history and the enduring reverence Muslims have for the Imam.

By engaging with these resources, one can gain a more profound understanding of not only the facts of Imam Abu Hanifa’s life, but also the philosophy and values that underlie the Hanafi madhhab. This knowledge ultimately strengthens one’s appreciation of Islamic law as a humane, dynamic system that serves to bring ease, justice, and spiritual beauty to our lives – just as Imam Abu Hanifa and his students intended.

Looking fora structured way to deepen your understanding of Islamic principles and theHanafi school? Jibreel, a mobile app, offers engaging, bite-sizedlessons on core Islamic knowledge, including wudu, ghusl, salah, zakat, andfasting, all rooted in traditional Hanafi sources. Download Jibreel today and begin your journey to mastering your Fard ‘Ayn.

.avif)

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.